Food Theory Series: Sugar

I'm one of those people that needs to know the how and the why behind everything. Learning and understanding the science behind food is the foundation to becoming the best chef you can be.

Few ingredients have shaped human civilization quite like sugar. Once considered a rare luxury reserved for kings and nobles, sugar has evolved into one of the most common staples in our kitchens. Long before refined sugar existed, humans used natural forms of sweetness from fruits, honey, and plant saps.

People learned to extract and crystallize sugar from the sugar cane’s juice. Today, sugar is produced in 121 countries and global production now exceeds 120 million tons a year. Approximately 70% is produced from sugar cane (a very tall grass with big stems that is largely grown in tropical countries). The remaining 30% is produced from sugar beet (a root crop grown mostly in the temperate zones in the north).

Sugar is the ingredient that delights our taste buds, powers our brains, and in many ways, defines our relationship with food. Sugar isn’t just about sweetness, it’s about chemistry. At its core, sugar is a carbohydrate. A simple molecule made of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. From a chemical perspective, sugars aren’t just about flavor, they’re reactive. When heated, they undergo caramelization, creating complex layers of taste and color. Combine them with proteins, and you get the Maillard reaction, the secret to golden brown cookies, toasty bread, and seared steak.

The Different Types of Sugar

There are many types of sugars, each one has different properties and are used for a specific reason.

- Glucose is a simple sugar and the most abundant carbohydrate. It is made from water and carbon dioxide during photosynthesis by plants. It’s used by plants to make cellulose, the most abundant carbohydrate in the world used by all living organisms. It’s used by the cells as energy.

- Inverted sugar is made by breaking down sucrose into its component parts, glucose and fructose through a process called hydrolysis. It is sweeter, more soluble, and more resistant to crystallization than sucrose. It's chemically similar to honey.

- Sucrose is ordinary granulated sugar, extracted from cane sugar or beet sugar. It has a sweetening power of 100% and is made up of 100% solids.

- Fructose is also known as “fruit sugar” because it primarily occurs naturally in many fruits. It also occurs naturally in other plant foods such as honey, sugar beets, sugar cane and vegetables. It’s the sweetest naturally occurring carbohydrate.

- Lactose is found in its natural state in milk. Some of us unfortunately can’t digest lactose very well. It’s sweetening power is very low.

Beyond sweetness, sugar controls texture, moisture and preservation. Remove sugar from a recipe, and the balance collapses. It’s not just less sweet, it’s chemically different.

● In baked goods, sugar keeps moisture in and creates tenderness by slowing gluten development.

● In ice cream, it lowers the freezing point, giving that smooth, scoopable texture.

● In jams and jellies, it binds with pectin to form the perfect gel.

Making toffee is as much chemistry as it is cooking.

When sugar and butter are heated to around 300°F (150°C) known as the hard crack stage, the sugar molecules break down and reorganize, creating complex caramelized flavors and that signature crunch. The addition of butter gives it richness and depth, making toffee taste far more luxurious than its humble ingredients suggest. A slight change in temperature, timing, or ratio can turn your toffee hard and glassy or soft and chewy. It’s a delicate dance between sweetness and science.

The hard-crack stage in candy making is when a sugar syrup reaches a temperature of 300°F resulting in a 99% sugar concentration with almost no water remaining. At this point, when a small amount of syrup is dropped into cold water, it forms hard, brittle threads that snap easily and are used for candies like brittle, lollipops, and toffee.

Toffee

Yield: 25-30 servings

Prep time: 10 minutes

Cook time: 20 minutes

Inactive time: 1 hour

Total time: 1 hour 30 minutes

1 pound butter

2 cups granulated sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

1 cup semisweet or bittersweet chocolate

1 cup finely chopped almonds - optional

Flaky salt - optional

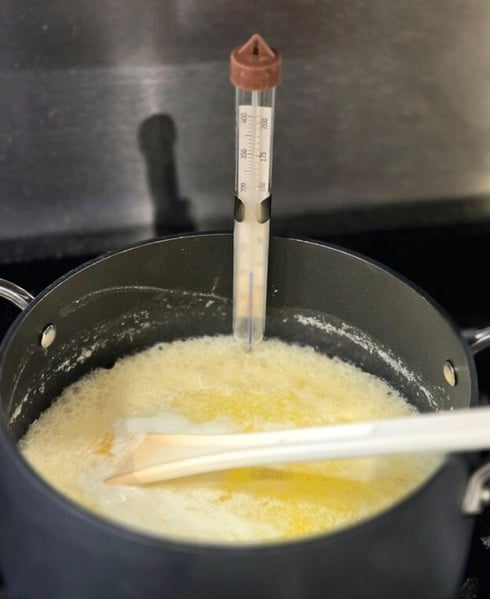

1. In a medium size pot over medium heat, place butter, sugar and salt.

2. Stir the mixture gently until the sugar is dissolved.

3. Allow the mixture to reach 285 degrees on a candy thermometer.

4. Line a 9x13 sheet tray or baking dish with parchment paper. Make sure the edges of the parchment paper are hanging over the long sides of the pan. (This will help it release out of the pan easier.)

5. Once the mixture reaches 285 degrees, turn off the heat. The temperature will rise to 300 degrees and once it does, pour into the prepared pan.

6. Let the toffee sit for 2-3 minutes to set slightly.

7. Sprinkle chocolate chips over the top in an even layer. Once the chocolate starts to melt, smooth it out over the top.

8. Sprinkle with almonds and flaky salt (optional).

9. Let the toffee fully cool - at least 1 hour.

10. Release the toffee out of the pan, use a knife to break it into your desired serving sizes.

11. Store in an air-tight container or sealed bags.

This is one of my favorite things to make around the holidays and I assure you, it is so simple. Making candy is an art, and it is sure to impress just about everyone.

To learn how to make other holiday treats, don't miss all of our classes at The Chopping Block:

- Hands-On Homemade Holiday Gifts on Saturday, December 20 at 10am

- Hands-On Family Festive Baking on Sunday, December 21 at 10am

- Hands-On Classic Holiday Cookies on Sunday, December 21 at 2:30pm